Ghana’s recent macroeconomic gains are the results of both hard work and understanding of the importance of transferable lessons, especially from the Asian Miracle.

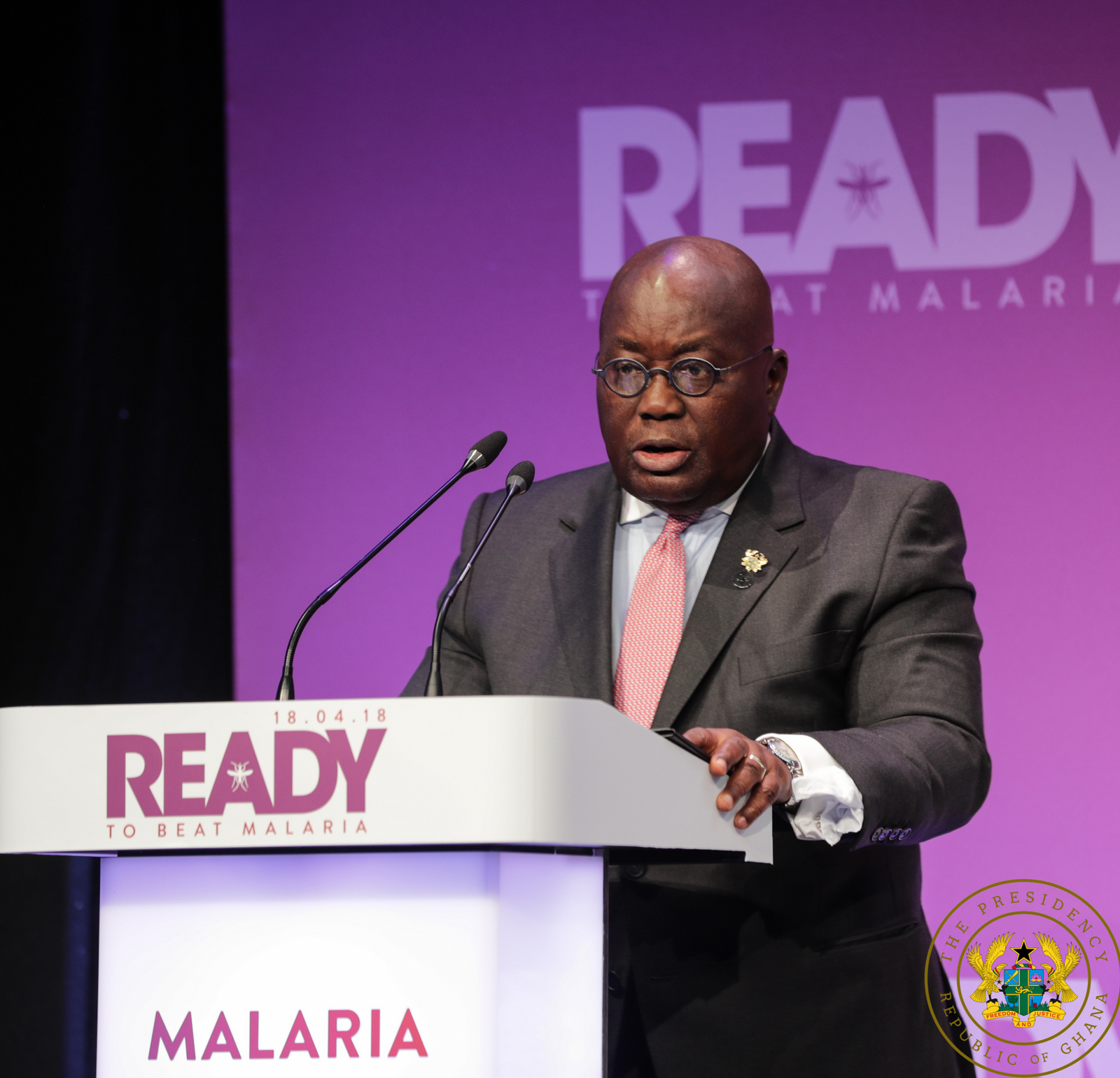

Drawing inspiration from the Asian model that produced the Asian Miracle, the macroeconomic gains registered by the Akufo-Addo government is the result of interactions between public and private triggered by a modern system.

The Asian Miracle highlights the quick transitioning of a set of countries from underdeveloped economies to developed ones. On the one hand, the success of what is known as the Asian model came on the back of hard work and discipline, a culture that sacrifices the present for future gains, according to former Singaporean Prime Minister, Lee Kwan Yew. And on the other hand, that success was supported by a system that ensured fruitful interactions between the public and corporate sectors.

Although Yew doubted the success of the Asian model outside the Asian region due that model’s endogenous character, economists agree that the model offers a set of systems that are flexible, modular and transferable. Yew’s generalisation failed to consider the composite transferable lessons embedded in the Asian (or the developmental state) model. This is especially because the Asian model, according to Ebohon, an economist, offers a tripodal governance structure.

Ebohon splits the developmental state’s governance structure into three estates: political leadership; techno-structure; and autonomous bureaucracy. So while Yew suggests that certain ‘driving forces’ that pushed the ‘Asian Miracle’ may be ‘absent’ in certain liberalising economies, the governance structure that underpins the developmental state (Asian) model makes it compatible with countries like Ghana, which shares similar characteristics with countries like Singapore and Malaysia. Our colonial trajectory and immediate post-colonial economies are two cases in point.

One of the characteristics of the Asian Miracle is the developmental state’s approach to regulating information asymmetry, where there is a dynamic and complementary relationship between the public and private sectors. Working together is a no-brainer, especially in situations where the success of industrial policies is dependent on how the public and private sectors interact. An example is the one-district-one-factory policy, which is embedded in the Ghana Beyond Aid vision.

To understand the Akufo-Addo administration’s creative approach to the developmental state’s tripodal governance structure calls for an understanding of the relationship between three estates:

1• The political estate (the president and ministerial body) provides the vision;

2• The bureaucratic estate (civil servants) embodies an autonomous bureaucracy that exhibits a highly selective meritocratic culture and long-term career possibilities to undermine self-interest;

3• Techno-structure (technical advisors) essentially comprises those who contribute specialised knowledge to both economic and production systems and also wield a controlling force over the corporate entity.

In order to prevent information asymmetries, in other words a bridging the gap between the private and public sectors, it is vital to create a dynamism where the two complement each other in a space that encourages the creation of endogenous and modern structures. It is a technical approach that undermines Lee Kwan Yu’s misgivings about the success of the Asian model in other regions.

An understanding of this system and how it works brings a fact to the fore: technical advisers don’t steal the jobs of bureaucrats, as the two are complementary.

Akufo-Addo’s tripodal approach has so far engendered positive results in an economy that was brought to it fiscal knees by the former government. Considering the macroeconomic gains made in the past 16 months alone, it is clear that a continued positive performance carried by the three estates promises to lead to the Ghanaian miracle.

By Prince Moses