Someone has said, and I think it is true, there is no true history. History is often the result of our selective and collective amnesia. In this regard, there is none to whom our history has been so unkind to as it has been to K.A Gbedemah. His efforts in our independence movement are often overshadowed by Nkrumah. We credit Nkrumah with the Akosombo Dam but perhaps, it is to Gbedemah that the credit belongs to.

The Volta River Dam was not the brainchild of Nkrumah in the way our history books emphasise. It had been in the offing for a while, at least since the 1920s. The British wanted cheap power to refine Ghana’s bauxite into aluminium to feed the empire’s industries. Even as independence beckoned, the enthusiasm of the British did not dim and the dam may well have been built as initially planned. However, in 1956, events far afield served as a cautionary take for the British and dimmed their enthusiasm.

In 1956 Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal. This caused an international crisis which ended in the British and the French withdrawing in humiliation with their imperial tails between their legs. This event together with the spiralling costs caused the British to reconsider their involvement and support for the project. The project was effectively shelved and may well have been but for a racist incident in the United States.

In 1957, K.A Gbedemah who was Finance Minister was invited to give a talk at the Maryland State College in the US on the then newly independent Ghana. He arrived and drove himself from New York to Maryland. On the way, he stopped for refreshment at a diner, Howard Johnson’s restaurant in Delaware. He was travelling with his secretary, an African American. Gbedemah entered the restaurant and asked for two glasses of orange juice; one for himself and the other for his secretary.

The waitress dutifully served the drinks and proceeded to tell them that they could not stay at the restaurant. Gbedemah was taken aback and sought to know why his money was good enough to pay for the drinks but he was not good enough to sit at the diner. The waitress turned around and reported the incident to her manager who came out and laid out the law: “Gentlemen I am sorry, because of your color, you can’t drink in here”.

Gbedemah was incensed. He was the minister of a sovereign state and he was not allowed to sit and enjoy a glass of orange juice because his skin had the wrong shade! Gbedemah left but only after making the manager aware that this was not going to be the end of the matter.

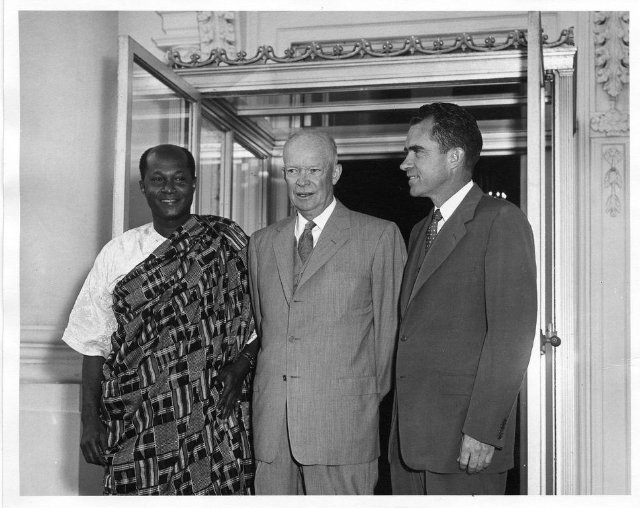

Back then, Ghana was a novelty, a new independent state and insulting Ghana’s finance minister was not a small matter. By the next day, the story made global headlines. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr whom Gbedemah had previously hosted in Accra wrote to Gbedemah to sympathize with him. The American president, Eisenhower in a bid to diffuse the diplomatic situation invited Gbedemah to the White House for breakfast. Present at the meeting was Richard Nixon who at the time was the vice president of the US. Months earlier Richard Nixon had led the American delegation to the independence celebrations in Accra.

There is, therefore, a fair chance that this breakfast meeting at the white house was not the first encounter between Richard Nixon and Gbedemah. Amid the apologies, Gbedemah slid in discussion around the stalled Akosombo Dam. The Americans were on the lookout to win the hearts and minds of the newly independent African state and this offered a fine opportunity. Eisenhower tasked Nixon to put Gbedemah in touch with the State Department. Subsequently, the Kaiser corporation got involved and the Volta River Dam project was given a new lease of life.

History has not been kind to Gbedemah. At least our history has not been. A true patriot, he was not afraid to go full throttle in his criticism of Nkrumah’s later catastrophic handling of the economy. Nkrumah forced Gbedemah to resign and eventually to go to exile. History would have been different if Gbedemah had been an opportunist. He could have usurped Nkrumah as the leader of the CPP at the time when Nkrumah was the guest of the British at the James town prison. Gbedemah was selfless, seeking the larger good where others sought their parochial interest.

By Emmanuel Adomako