One day in August 1995 a man called Foutanga Babani Sissoko walked into the head office of the Dubai Islamic Bank and asked for a loan to buy a car. The manager agreed, and Sissoko invited him home for dinner. It was the prelude, writes the BBC’s Brigitte Scheffer, to one of the most audacious confidence tricks of all time.

Over dinner, Sissoko made a startling claim. He told the bank manager, Mohammed Ayoub, that he had magic powers. With these powers, he could take a sum of money and double it. He invited his Emirati friend to come again, and to bring some cash.

Black magic is condemned by Islam as blasphemous. Even so, there’s still a widespread belief in it, and Ayoub was taken in by the colourful and mysterious businessman from a remote village in Mali.

When he arrived at Sissoko’s house the next time, carrying his money, a man burst out of a room saying a spirit – a djinn – had just attacked him. He warned Ayoub not to anger the djinn, for fear his money would not be doubled. So Ayoub left his cash in the magic room, and waited.

He said he saw lights and smoke. He heard the voices of spirits. Then there was silence.

The money had indeed doubled.

Ayoub was delighted – and the heist could begin.

“He believed it was Black Magic – that Mr Sissoko could double the money,” says Alan Fine, a Miami attorney the bank later asked to investigate the crime.

“So he would send money to Mr Sissoko – the bank’s money – and he expected it to come back in double the amount.”

Between 1995 and 1998, Ayoub made 183 transfers into Sissoko’s accounts around the world. Sissoko was also running up big credit card bills – in the millions according to Fine – which Ayoub would settle on his behalf.

In 1998 I was living in Dubai, and I heard rumours that the bank was in trouble. When a newspaper reported that the bank was having cashflow problems, crowds of people gathered outside, waiting to withdraw their money.

The Dubai authorities downplayed the crisis. They called it “a little difficulty that did not lead to any financial losses either in the bank’s investments or depositors’ accounts”.

But this wasn’t true.

“The people who owned the bank took a huge, huge hit. It was not covered by insurance,” says Fine. “The bank was saved because the government stepped in to help. But they gave up a lot of their equity in the bank for that to happen.”

And where was Foutanga Babani Sissoko? By this time, he was far away.

One of the beauties of his scheme was that he did not need to be in Dubai to keep receiving the money.

In November 1995, only weeks after putting on the magic display for Mohammed Ayoub, Sissoko visited another bank in New York, and did much more than open an account.

“He walked into Citibank one day, no appointment, met a teller and he ended up marrying her,” says Alan Fine. “And there’s reason to believe she made his relationship with Citibank more comfortable, and he ended up opening an account there through which, from memory, I’m just going to say more than $100m was wire transferred into the United States.”

In fact, according to a case brought by the Dubai Islamic Bank against Citibank, more than $151m “was debited by Citibank from DIB’s correspondent account without proper authorisation”. The case was later dropped.

Sissoko paid his new wife more than half a million dollars for her help.

“I don’t know under what legal regime he married her but he called her a wife and she believed she was a wife,” says Fine.

“She understood that there were many other wives. Some from Africa, some from Miami, some from New York.”

With the bank’s money rolling in, Sissoko could fulfil his dream of opening an airline for West Africa. He bought a used Hawker-Siddeley 125 and a pair of old Boeing 727s. This was the birth of Air Dabia, named after his village in Mali.

But in July 1996, Sissoko made a serious mistake as he tried to buy two Huey helicopters dating from the Vietnam War, for reasons that remain unclear.

“His explanation of why he wanted them was emergency air ambulance. But the helicopters he was looking at were pretty big helicopters, they were not the kind that you see running back and forth to hospitals and trauma centres in the United States, they were much bigger than that,” says Fine.

Because they could be refitted as gunships, the helicopters needed a special export licence. Sissoko’s men tried to speed things up by offering a $30,000 bribe to a customs officer. Instead, they got themselves arrested. And Interpol issued a warrant for Sissoko’s arrest too. He was caught in Geneva, where he’d gone to open another bank account.

Tom Spencer, a Miami lawyer who was asked to represent Sissoko, vividly remembers going to meet him in Geneva’s Champ-Dollon prison.

“I talked with the prison warden, who asked me whether or not Sissoko was going to go to the United States,” Spencer says.

“I said, ‘Well, you know, we’ll see.’ And he said, ‘Well, please delay it as long as possible.’ And I said, ‘Well why?’ And he said, ‘Because he’s flying in fantastic meals from Paris every night, for us.’ And that was my first bizarre encounter with Baba Sissoko.”

Sissoko was quickly extradited to the US, where he started to mobilise influential supporters.

The readiness of diplomats to vouch for Sissoko shocked the judge presiding over his bail hearing. And Tom Spencer was stunned when a former US senator, Birch Bayh, announced he was joining Sissoko’s defence team.

“Well, you have to ask yourself, why would anyone get involved for a foreign national who has no apparent value to the United States?” says Fine. “I don’t know the answer to the question. But it’s an interesting one to pose.”

The US government wanted Sissoko held in custody, but he was bailed for $20m (£14.5m) – a Florida record at the time.

Then he went on a spending spree.

His defence team was rewarded with Mercedes or Jaguar cars. But that was just the start.

Sissoko spent half a million dollars in one jewellery store alone, Fine recalls, and hundreds of thousands in others. In one men’s clothing store he spent more than $150,000.

“He would come in and buy two three four cars at the same time, come back another week and buy two three four cars at the same time. It was just, the money was like wind,” says car dealer Ronil Dufrene.

He calculates that he sold Sissoko between 30 and 35 cars in total.

Sissoko became a Miami celebrity. He already had several wives, but that didn’t stop him marrying more – and housing them in some of the 23 apartments he rented in the city.

“‘Playboy’ is the right word to describe him. Because he is very elegant. And handsome. And he dresses with great style. He blew a lot of money in Miami,” says Sissoko’s cousin, Makan Mousa.

Sissoko was also giving away large sums to good causes. His trial was approaching, and he knew the value of good publicity. In one case witnessed by his cousin, he gave £300,000 ($413,000) to a high-school band that needed money to travel to New York for a Thanksgiving Day parade.

Another of his defence lawyers, Prof H T Smith, remembers that on Thursdays he would drive around giving money to homeless people.

“I was thinking, is this some modern day Robin Hood? Why would you steal money and give it away? It doesn’t make any sense,” he says.

“The [Miami] Herald did a story just after he left, and I think – I don’t want to exaggerate but I think they said they could chronicle like $14m he gave away. He was only here 10 months. That’s over a million dollars a month.”

Alan Fine took a slightly more cynical view.

“So much of what he did was for image and to perpetuate a belief that he was a very powerful man and fabulously wealthy. He would give away money, but… to my knowledge it was never done in a way that he didn’t get publicity for it.”

Despite this PR drive, when Sissoko’s case came to court he disregarded his lawyers’ advice and pleaded guilty.

Maybe he calculated that this would provoke fewer questions about his finances.

The sentence was 43 days in prison and a $250,000 fine – paid, of course, by the Dubai Islamic Bank, though without its knowledge.

After serving only half this sentence, he was given early release in return for a $1m payment to a homeless shelter. The rest he was meant to serve under house arrest in Mali.

Instead he returned home to a hero’s welcome.

It was around this time that the Dubai Islamic Bank’s auditors began to notice that something was wrong. Ayoub was getting nervous, and Sissoko had stopped answering his calls.

Finally he confessed to a colleague, who asked how much was missing. Too ashamed to say, Ayoub wrote it on a scrap of paper – 890 million dirhams, the equivalent of $242m (£175m).

He was found guilty of fraud and given three years in jail. It’s rumoured he was also forced to undergo an exorcism, to cure him of his belief in black magic.

Sissoko has never faced justice. In his absence, a Dubai court sentenced him to three years for fraud and practising magic. Interpol issued an arrest warrant and he remains a wanted man.

I found transcripts from other trials at which Sissoko failed to appear, including one in Paris. His lawyer claimed he was a scapegoat for Ayoub’s actions and the bank’s money had gone elsewhere, but the court didn’t swallow it and convicted him of money-laundering.

For 12 years, between 2002 and 2014, Sissoko was a member of parliament in Mali, which gave him immunity from prosecution. For the last four years, no longer an MP, he has been protected by the fact that Mali has no extradition treaty with any other country.

The Dubai Islamic Bank, nonetheless, is still pursuing him through the courts.

I flew to Mali’s capital, Bamako, to find people who might tell me about Sissoko.

I tracked down his seamstress, who remembered him fondly.

“The last time I saw him, two or three years ago, I made him a suitcase of clothes. If he didn’t give out presents, he wasn’t happy. It’s his style. He loves to give things to people,” she said.

I also found his driver, Lukali Ibrahim.

“The good thing about him is that when things are going well you can expect a lot of presents from him. He likes to help people with their problems,” he said. “The bad thing, I can tell you a few. This is someone who always gives people hope but instead of telling you the truth, he’s just leading you on.”

In the market I found a goldsmith who had only praise for a client who would call and ask him to make presents for his friends.

I also heard that he could be found living near his native village, Dabia, which had given its name to Sissoko’s short-lived airline, near Mali’s border with Guinea and Senegal.

After a long drive I found a house that fitted the description I’d been given.

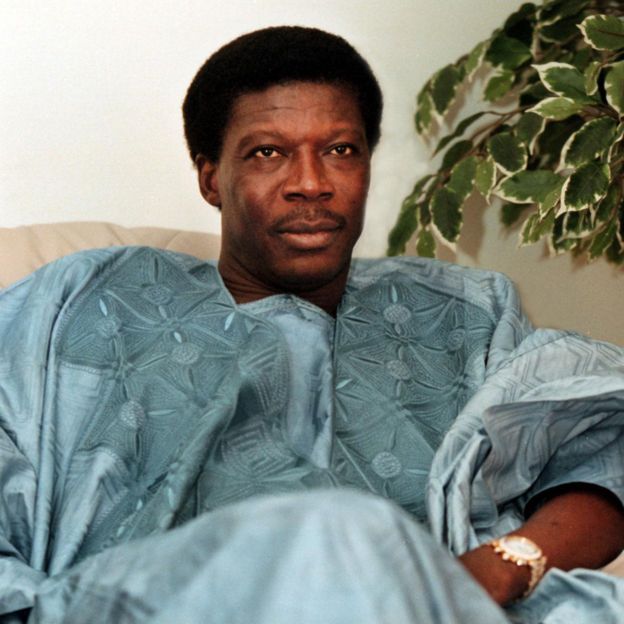

Suddenly, surrounded by armed guards, there he was. Babani Sissoko, in person, now perhaps 70 years old.

He agreed to an interview. The atmosphere was edgy and slightly surreal. He began by telling me about his entry into the world.

“My name is Sissoko Foutanga Dit Babani. You know, the day I was born all the villages round here burned down. The villagers went round shouting, ‘Marietto has had a boy.’ The fire leapt and leapt. There used to be a lot of bush around.”

He then talked about his efforts to rebuild the village, which began in 1985, and about the money he made. At one point he had been worth $400m, he said.

Eventually, I asked about the $242m he had received from the Dubai Islamic Bank.

“Madame, this $242m, this is a slightly crazy story. The gentlemen from the bank should explain how they lost all that money. I mean the $242m. Listen, how could that money have left the bank the way it did? That’s the problem. It’s not this man alone [Ayoub] who authorises the transfers. When the bank transfers money it’s not just one person who does it. Several people have to do it.”

I pointed out to him that Mohammed Ayoub had claimed at his trial that Sissoko had put him under a spell.

“The gentleman you’re talking about, I’ve seen him and met him,” he said.

But the heist, he denied.

“The only contact I had with him was when I went to buy a car. The bank bought it for me and I repaid the loan. It was a Japanese car.”

Had he controlled people by means of black magic?

“Madame, if a person had that kind of power, why would he work? If you have that kind of power you can stay where you are and rob all the banks of the world. In the United States, France, Germany, everywhere. Even here in Africa. You could rob all the banks you want.”

I asked him if he was still rich.

His answer was blunt.

“No I’m not rich any longer. I’m poor.”

Defying Interpol, Sissoko has spent a remarkable 20 years on the run, even if he has squandered all his money and can never leave Mali.

He has never spent a day in jail for the black magic bank heist.

Source: BBC