The death of South Africa’s veteran anti-apartheid activist Winnie Madikizela-Mandela at the age of 81 has sparked a national debate about how she should be remembered.

The more traditional sections of society, including her staunch supporters, want us to remember her as a faultless woman.

Others, particularly those who are still in the trenches fighting the old battles in favour of white supremacy, want us to remember Mrs Madikizela-Mandela as a violent and deeply flawed individual.

But anyone who wants to truly understand the Winnie Madikizela-Mandela I knew needs to go back in time and trace the steps of humiliation she suffered under the racist system of apartheid.

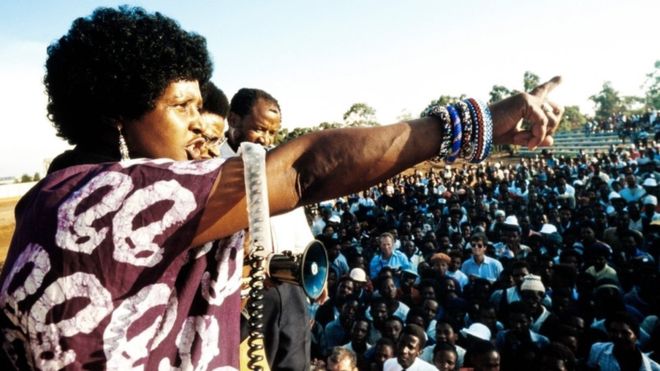

She was a freedom fighter; a revolutionary who was at the coalface of the anti-apartheid struggle – not an armchair activist who waged a revolution on Twitter or Facebook.

She was left to raise two young daughters when her husband of four years, Nelson Mandela, was arrested in 1962 and sentenced to life in prison on the notorious Robben Island prison.

An activist in her own right, Mrs Madikizela-Mandela was once arrested in her pyjamas. The police refused to grant her permission to get her relative, who lived a block away, to come and stay with her children.

Torture chamber

In 1969, she was locked in solitary confinement for 491 days. She was even left in her cell when she was on her period, without sanitary towels.

Her cell was adjacent to a torture chamber.

“Prisoner number 1323/69” wrote in her diary, which was later published in a book entitled 491 Days, that the screams of women being beaten from across the walls will never leave her mind.

Later, at a time when many other anti-apartheid leaders were languishing in jail or in exile, she not only represented the liberation movement. She was The Movement.

When she moved, the frontline moved with her. She did not fill the vacuum left by Mr Mandela. She simply took her rightful place at the centre of the battle for the freedom of black people.

When the apartheid regime found her to be too powerful to handle, it resorted to banishing her from her home in the commercial capital, Johannesburg, to the small rural town of Brandfort in what was then the Orange Free State, a bastion of white supremacy.

She was not allowed to receive visitors, but she travelled daily to the local post office to make phone calls telling the world about the brutality of the apartheid system.

Beautiful and charismatic

Having read and listened to the many comments since her passing on Monday, it became clear to me that some people either do not know history or they have collective amnesia.

One example is the reaction of former newspaper columnist David Bullard who wrote on Twitter: “So, after an educational night on Twitter, we’re all agreed then. Winnie was a saint who fought bravely against apartheid and only set fire to people or had kids murdered when it was absolutely necessary.”

Such people seem to have forgotten the trauma Mrs Madikizela-Mandela experienced at the hands of those who enforced some of the most racist and sexist laws the world has ever seen.

However, her character, sheer strength and willpower could not be suppressed.

In January 1985, US Senator Edward Kennedy visited her in Brandfort, describing her as someone who was “very courageous and was very concerned for her country”.

It was a poignant moment – an African woman, removed from society as punishment for asking for basic human rights, getting a visit from one of the most powerful politicians in the US. This sent a clear message that she – and black people – were not alone in the struggle against apartheid.

Mrs Madikizela-Mandela was not just a fearless freedom fighter, she was incredibly beautiful. Even if you were an apartheid-era policeman who met her, you would not forget her face, eyes, and beautiful smile. She also had a unique charisma, and was in many ways, regal.

But she was not perfect. She had her flaws.

She was convicted of fraud and being an accessory to kidnapping.

Any fair-minded person cannot reflect on Mrs Madikizela-Mandela’s life without mentioning 14-year-old Stompie Sepei. He died at the hands of her scandal-prone football club, bodyguards and driver, after being falsely accused of being an apartheid spy.

Her support for “necklacing” suspected traitors by putting a tyre around their necks, dousing them with petrol and setting them alight also put her in direct conflict with her comrades.

‘Apartheid’s legacy’

Following her death, anti-apartheid activist and opposition politician Mosiuoa Lekota said: “Those who did nothing under apartheid never made mistakes.”

All these experiences and more left her traumatised. Some suspect she suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, which was never treated because she went from one brutal treatment to the next without delay.

I will never forget the day Archbishop Desmond Tutu pleaded with her at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, formed to heal the wounds of apartheid, to say “sorry” for all the things that had gone wrong. She only agreed to acknowledge that sometimes things “went horribly wrong.”

Author Charlene Smith, who knew Mrs Madikizela-Mandela from the mid-1970s, could not have put it more succinctly when she posted on Facebook:

“Winnie is the Conscience of a Nation that has already forgotten the tragedy of apartheid history; even in her death, people do not realize how she suffered, how damaged she became and how it hurt her and those who cared for her most.

“South Africa today has one of the worst crime rates in the world, it has millions of damaged people – they are apartheid’s legacy. It is in remembering and healing a wounded people that we honor the legacy of Winnie Madikizela Mandela. Sleep with the angels Nomzamo.”

Source: